This post is based on the podcast – 11 Things That Confuse Veterans In The Civilian World

This post is based on the podcast – 11 Things That Confuse Veterans In The Civilian World

Tom: Hey, everyone! Tom Morkes here and I’m sitting down with Antonio Centeno, part of the High Speed Low Drag team. How’s it going, Antonio?

Antonio: Hey! It’s good to be here, Tom.

Tom: Hey! Yeah, we’re going to be talking about the 11 things that Vets find confusing about the civilian world today, and we’re going to take it right from the top starting with — and this is stuff that Antonio and I have talked about before, and John. It’s the things that we see veterans essentially making mistakes about in the civilian world.

They come at it from a certain perspective from being in the military and getting in the civilian world can be kind of really — it can be a tough transition for a lot of Vets. I know even myself, I felt like it was pretty tough making the change, making the transition.

And so, we want to touch on what those things are, the 11 main things that Vets find confusing about the civilian world, and ways that you can actually work around them and essentially fix this to them or what you can do to find stability and figure out a way forward where you can actually succeed in the civilian world.

Antonio: And there’s nothing to be ashamed of having these things that are confusing to you. Think about if someone’s visiting a Navy ship and they’re walking around and if they’re asking where the bathroom’s at, you tell them that the head is right down the hall or to head towards the bowel of the ship, you just use terms in there which they’re not familiar with.

What’s a head? Where is the bowel of the ship? All of a sudden, you’re using terminology that’s very familiar with you, but it throws them for a loop. Many guys, they’ve been serving for 20 years, 10 years, they get out and that’s what they know. All of a sudden, they’re facing these things in the civilian world that they’ve never had to before.

You shouldn’t be ashamed of that. However, it is something that you want to correct as soon as possible in terms of at least having an understanding. This doesn’t apply to everyone, but it definitely is something you have to be on your guard about because the first one, I think, is a great example.

Now, there are many civilians out there that I can tell and I can talk with, and if they tell me they’re going to do something, they’re going to do it. However, there are many — and it seems like more than 50% — it seems like we say one thing to them and they don’t necessarily take it in seriously.

A soldier’s word is his bond. A coasty stands by what he says. Literally, in the Marine, our motto is “Always faithful.” However, in the civilian world, it can be something that you ask somebody to do something and they just don’t do it and there are no repercussions here.

Tom: Yeah. One of the things I think that compounds this issue is the nature of that. In the service, how often do you work with contracts? You don’t, do you? As far as working with other soldiers — like in the Army, I was working with other soldiers, working with other officers. It’s not like I had to work contracts with them.

It was, “Hey, we need vehicles over here,” “Hey, we need this moved here.” I did a lot of logistics and transportation stuff, so if somebody needed it, they’d put in an order, a work order or something like that or some kind of paperwork maybe, but it was never contractually based like I had to sign it to confirm it on my end and vice versa. Check This Out to know about the company that offers the best logistics services in this city.

So getting on to the civilian world — or I guess to say that then is that we basically took everything at face value. And then when you get in to the civilian world, when you’re working with other people, it’s not like that. You actually have to — at some point and in many cases, you have to get contracts and agreements written down, and that’s kind of foreign to a lot of people —

Antonio: And it’s not just in the business world. It’s simply sometimes with personal relationships or people that you meet. I have a number of friends in California and they will talk with somebody like, “Hey! Okay, I’ll see you here a little bit later. Yeah, see you later.” Okay. They said they would see you later and you thought you agreed to meet at a point or at a coffee shop or a place for dinner, and they just don’t show up. They completely flake on you.

In the military, there are repercussions. Literally someone that is doing this repeatedly can be brought up with nonjudicial punishment. As an officer, literally if the commanding officer asks you to do something, he’s not really asking. You do it and if you don’t, then you could lose your command, but there aren’t those punishments in the civilian world.

I’m not saying that’s wrong. I love the civilian world. It is what it is, but it is something that it can be very frustrating. Again, realize that as military men and women, we often take each other at face value. That’s not always the case when you transition out.

Another thing that we see, and we’ll move on to point number two, is narcissism. This is where people are very much fixated on themselves, on getting credit, on in a sense covering their own backside. In the military, it’s a little bit different. It’s really about mission accomplishment.

Another thing that we see, and we’ll move on to point number two, is narcissism. This is where people are very much fixated on themselves, on getting credit, on in a sense covering their own backside. In the military, it’s a little bit different. It’s really about mission accomplishment.

If a Harrier is going up, the pilot, he even tries to oftentimes defer credit to his crew and to everyone that worked on the airplane from the guy that’s basically making sure everything is screwed on the right way when they’re doing the repairs. He realizes that he’s just part of a team, while in the civilian world especially in the business environment, you see a lot people trying to claim credit for something that they may not necessarily have even done themselves.

Tom: Yeah, it’s so true. Again, it’s one of those situations where I wouldn’t say that it’s right or wrong, but just that it is what it is. But to say that I find this a lot with veterans, when they get out, that they are so humble compared to the status quo that’s out there, and actually to the point where it could be detrimental because I meet veterans and they have really great accomplishments, but they won’t even talk about them.

In the civilian world, it’s expected. If you don’t share information about yourself, you’re not going to get the job or you’re not going to get to sit down with somebody. People will ignore you if you’re not willing to talk about yourself, and it’s not a great situation for a lot of Vets. I understand they want to be humble, but there’s a fine line there between being so humble and just not saying anything about yourself and missing out on opportunities, and then being braggadocious or being narcissistic, which is that other extreme, but I don’t know. What are your thoughts on that, Antonio?

Antonio: I agree, Tom. I think you need to strike a balance and you need to pay attention to the situation. If you’re in an interview, then you need to make a point and be able to show the value that you are going to bring to the company. If you’re interacting with people and you’re working with your peers, you also need to be able to bring things — and we’ll talk about this a little bit later — but to be able to also talk about it in a language that they understand.

Avoiding narcissism, I think, is usually not a problem for most Vets. However, dealing with it and also being able to make sure that you have your name on certain documents if they are going to be — if you put a lot of work into something, you want to also make sure that people understand you got credit for that. We’ll talk a little bit more about ways and tactics that you can actually let people know how much time you’re putting in and the amount of work, and who in a sense should get credit for this.

Let’s move on to point number three, the importance of physical goods and image. Now, I remember when I left the Marine Corps, everything I owned could fit into my Chevy truck, and I didn’t have a full — I’m not talking about a trailer and extended cab. I had a short bed truck and I was always proud of that. I could, at a moment’s notice, be stationed to the other side of the country or be deployed and I could get everything into a storage unit.

I think we saw the value — you see a lot of people, in a sense — to be blunt, when you see young people losing their lives, you realize how valuable life is and how unimportant physical goods are. That’s something that has stuck with me and I think has really given me a better appreciation for life and how important it is.

Unfortunately, not just the United States, but I think many places throughout the world, are becoming very consumer-driven and it’s something where you’re going to — don’t be surprised when the kind of car that you drive, the type of clothing that you wear — and I’m in the style industry, so I see this all the time — the kind of house that you own, many times, you’re putting that as a higher level of importance than the character of the person that actually owns the stuff.

Tom: Yeah. It’s one of those situations that’s almost a catch-22.

I think for a lot of Vets, it’s something that’s again depressing because you get out of the military and you realize that so many things seem superficial, at least on the outside when you enter the civilian world.

We’ll get into some other aspects of that, too, but specifically about the importance of physical goods and image, I guess it’s something that I try to avoid at all costs because I don’t want to get tied up in that or wrapped up in that.

I think that it’s more important to be good at what you do and to be a person of character and to let that shine through than to try to gain some status by buying the right clothes or buying the right car. I don’t know though, Antonio. You are the style guy here, so you tell me where that fine line is.

Antonio: Well, it depends on the individual. If you’re a master electrician or a master plumber, do I think you need to own a suite, a fancy car and all that stuff? No, but you do need to be able to send a signal of competency and trust.

Antonio: Well, it depends on the individual. If you’re a master electrician or a master plumber, do I think you need to own a suite, a fancy car and all that stuff? No, but you do need to be able to send a signal of competency and trust.

I think you should leverage the fact that I’m used to wearing the uniform. I’m starting a plumbing business. We’re going to have a company uniform, not because I want to regiment, but I do want to control. I don’t want my guys getting injured when they’re under working on pipes and get burned or something if hot water shoots out because they weren’t wearing a proper cotton work shirt that covers their sleeves. Little things like that, to me, that’s where it’s practical and it makes sense.

As military guys, I think we’ve — Ronald Reagan, he said this at least for the Marines, or at least we quote him as saying it, but he said, “Many people go through life wondering if they made a difference.” The Marines don’t have that problem, and I think it’s the same thing for the Army, for airmen, for our sailors, for men that have served in National Guard or the coastguard.

It’s one of those things. We are very comfortable and confident that we’ve contributed. We’ve earned our citizenship. We’ve earned our place and we’ve put in our time. Many people, I think, who are out there, they haven’t had that and they’re trying to fill that void, which I think is often — in many of our hearts, they’re trying to fill that with physical goods or image or the perception that somehow they’ve made it. That’s something you just have to be aware of. I’m not going to say we’re going to change it, but I am saying it’s something — don’t fall into the trap and be aware that that is out there.

Now, layoffs and being fired, I would say that in the military, we don’t see this very often, although recently we’ve seen in the US Army a number of officers just got pink slips and they’re downsizing. However, as an overall picture, if you’re a pretty hard charger, we can pretty much — the military has been around for hundreds of years, at least here in the United States. If you’re a hard charger, top of your class, you’re pretty much guaranteed you’re going to be taken care of. That’s not always the case in the civilian world.

Tom: Yeah, and it’s a real consideration. Again, being in the military is unique. Being in any sort of government agency or government job is unique in that way. It’s really hard to be fired, but all of a sudden, when you get into the civilian world, you’re going to have to actually think about your performances. I don’t think that will be an issue for, I’m guessing, probably 99% of people listening to this podcast right now.

It’s not going to be an issue for them because you’re probably the type of person who doesn’t screw around anyway and actually does your job and everything like that, but it’s still a consideration. You just have to be cognizant of it. It’s a different world in that respect and you could get cut if you don’t perform. And so, performance is what civilian employers look for. That’s really, I guess, all I have to say about that.

Hiring an employment lawyer from HKM to help you understand your responsibilities can save you from potentially having to go through a lawsuit. It can also help to ensure that your rights are protected.

Antonio: You can get cut because the company simply changes. Sometimes you’ve got a merger and two companies are coming together. Well, guess what? In a merger, there’s always a dominant player and one company is going to — basically, the reason for mergers in companies is to cut costs.

Basically, they want to consolidate their customers and they want to get rid of half of the people in probably one of the companies. They’ll keep some of the best people or who they choose. You could be a top performer and be part of a merger and all of a sudden, you find that the other guy, he’s with the company that simply is on top of the heap and you’re simply being cut, nothing you can do about this. I’ve seen this multiple times. And so, you’ve got to be flexible. You’ve got to always be sharpening your sword like this Longsword for sale and ready to jump ship.

Now, there are some companies out there that they’re doing a great job of taking care of their people, but that’s becoming fewer and far between. It used to be you could put in 30 years at GM, General Motors, or go to Ford. For the most part, a lot of that stuff is gone. In fact, the military is one of the last fortresses where you see long-term employment and the stability, which we’ve become used to.

Now, negotiating your salary, as a captain, let me ask. Tom — or as a lieutenant — were you ever able to negotiate your salary?

Tom: No. I wish, but I wasn’t.

Antonio: Yeah, so all first lieutenants pretty much get the same thing. In fact, if you think about it — if you think of what communism is, we actually had, I think, close to a form of communism in the military where you’re actually paid based off of need. Think about it. If you are married and you had five kids, you got paid more. It’s simply that you needed more.

Antonio: Yeah, so all first lieutenants pretty much get the same thing. In fact, if you think about it — if you think of what communism is, we actually had, I think, close to a form of communism in the military where you’re actually paid based off of need. Think about it. If you are married and you had five kids, you got paid more. It’s simply that you needed more.

I think it’s just because salary wasn’t that big of a deal, but we never had to negotiate our salary. It was pretty clear that based off of what you plug in to the machine, what you are going to get — if you’re in a combat zone, good thing you’re not paying taxes that month. That was always a cool thing. Every time the boats could go into a combat, yeah, that was a great thing. Everyone just got an extra bit of bump on their raise or on their pay scale.

In the civilian world, especially at the very beginning when you are initially hired and you have the most leverage, that’s when you have to negotiate for your salary. You have to determine the jobs that you’re going after, how much are they paying, and what’s the reward, and it’s not something that the guy making $100,000 is working twice as hard as the guy making $50,000. Sometimes the guy that made $100,000 and the guy that made $50,000 are doing the exact same job; one just negotiated better.

Tom: Yeah. So Antonio, how do you approach that then if you’re just getting out and you’re looking at a job? How do you approach that negotiation?

Antonio: The first thing you do is you educate yourself and be open to the fact that you know nothing about this. There are many great books. One of my favorites is “The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator”. This was my textbook when I was at the University of Texas getting my MBA.

I have to say, I took all those corporate finance accounting, all these other high-level MBA courses, but it was those soft skills — I actually teach some of these over at Real Men Real Style — but those soft skills and realizing that there are many things that are valuable because you don’t have to — we titled this one “Negotiating Your Salaries”, but there are other things that may be important to you and less important to the company.

So it’s about understanding that — if you’ve got two people fighting over a pie and then you realize that one of the people, he just wants the pie pan; the other person wants the pie. If they would’ve simply talked and explained to each other, they could both have walked away happy. Instead, they cut the whole thing in half, destroyed the pan, and the one guy goes hungry because he wanted the whole pie while the other one throws it away.

I think when you can start looking at things that way, you start to realize there’s more to the picture than just money. There’s also time-off. There’s vacation time. There are the hours that you work. There in a sense is the opportunity for bonus and to be able to earn based off of what — so these things, we’ve just never had to think about.

This is when you’re getting out. Whether you’re a 45-year-old lieutenant colonel or colonel, or you are a 22-year-old lance corporal, if you can open your mind to this, all of a sudden, you’re able to ask better questions and I think get a better salary or package whenever you work for a company, or start your own business.

Tom: Yeah, that’s good stuff. I think at a later segment, I think that might even be a good topic to go even in more depth about, but I think that’s great for right now.

Antonio: Thanks, Tom. All right, so let’s go to number six, translating your stories and experiences. I’ll let you handle this one because I think that you are fresh out and it’s one of those things when you tell people what you do and you use a certain jargon and they give you the blank eyes.

Tom: Yeah. Well, it’s funny, too. John Corcoran, our mutual friend, he wrote an article for Art of Manliness where he actually mentioned me in it, about how I’m able to tell my story without coming off cocky or anything like that.

What I did was, just in a nutshell, if anybody asked me what I did in the Army, I’d say, “Yeah, I was in the Army, a convoy security platoon leader in Iraq. In my last unit, I got paid to jump out of helicopters.” That’s about as detailed as I get unless people are really curious about how that worked.

Most people really aren’t, but that story in a nutshell lets people know. “Wow! You probably did some really cool stuff.” That’s all people really need to know. They really want to hear about the cool stuff. They don’t really want to hear your life story for the most part, so at least that was my experience.

Most people really aren’t, but that story in a nutshell lets people know. “Wow! You probably did some really cool stuff.” That’s all people really need to know. They really want to hear about the cool stuff. They don’t really want to hear your life story for the most part, so at least that was my experience.

From there, it gives the person you’re having conversation with — either your potential employer or just peers or whoever, just the people you meet — it piques their interest enough to have you stick around and keep talking. It’s a story that sticks.

That’s another thing as veterans. Remember we were talking in the beginning about being too humble and you don’t tell your stories and that could be a negative. I think it’s important to hone in on your story, your one or two-sentence story that makes you stand out a little bit. I don’t know, Antonio, what your thoughts are on that, but that’s how I perceive it.

Antonio: You hit it right on the head. You need to tell a story that sticks, keep it short, keep it relevant, and remember, it’s not about you. They truly don’t want to hear your five-minute to ten-minute overall story, and avoid the jargon.

“I went to OCS and I went to TBS we’re in MREs.” I know what those acronyms mean, but that person, the civilian, all of a sudden, his eyes are glossed over. He’s like, “I have no idea what language this guy is speaking. I’m worried that I could put him in front of a customer because he doesn’t obviously understand — it would take too much work to communicate.” So they’ll thank you for your service, they’ll shake your hand, and then they won’t hire you.

You need to make sure that you’re speaking their language and that you get an emotion across. When you tell me that you jumped out of helicopters, that’s very easy for me to imagine, Tom, and I think, “This guy isn’t afraid of anything.”

Tom: Exactly, even though I’m quaking in my boots, but that’s true. What’s funny, too, about that is — I’m glad you brought up the acronyms thing. It’s interesting because there’s no direct translation for a lot of the positions in the military.

If I was to say I was the S3 at one point, what does that mean? That only means something to less than 1% of the population maybe, but if I said, “I was in charge of operations for a battalion,” now maybe that’s closer, or maybe even refining it a little bit better like, “I was in charge of planning the training,” et cetera, “of X number of soldiers,” all of a sudden, it’s something that’s translatable.

Antonio: You just talked about three different levels. You go from S3 to operations to planning. We all know that those are the same thing, S3 shops, plan for the entire battalion. I know a battalion, at least in the Marine Corps, is going to be a thousand people whether or not it’s reinforced higher or lower, but you’ve got to explain those details.

That last one is the one that’s going to resonate. The middle one, that will translate across services. That first one usually sometimes can be even — there are Marines I’m sure that you speak with, Tom, who they’ll start spitting out things like, “I think I know what that means, but not sure,” like it doesn’t always translate over.

Tom: Exactly.

Antonio: Number seven, let’s get into business language. Tom, you’ve made the jump recently. How have you been in a sense picking up the language of business?

Antonio: Number seven, let’s get into business language. Tom, you’ve made the jump recently. How have you been in a sense picking up the language of business?

Tom: It is a great question. One is reading and two is listening to podcasts. I guess those are both encompassed underneath education, actually going out and trying to learn things and being proactive about it. So even before I got out, I was reading a lot of business books and then also listening to podcasts.

I remember John’s podcast, “Entrepreneur on Fire“, was one of the podcasts I listened to in the last few months of being in the Army, and you start to pick stuff up. It’s the best way to learn a language, is immersion. And so, when you take that mindset of immersion in business, whether you want to get a great job or you want to start your own company, you need to immerse yourself in it.

It’s just like in the Army or in the military, how difficult it is when you first get in there, to learn what all the acronyms mean. There’s maybe not as many things that you have to figure out in the civilian world, but there’s going to be its own set of terms and you’re going to seem like an outsider if you don’t use them or understand them or apply them correctly, so, education first and foremost.

Antonio: Great, and that’s a great way to start. I did the same exact thing before going to business school. I’ve read a few books. There’s a lot more to that, but you’ve got to start.

How to find a new career path, now, I can tell you in the Marine Corps, I was S1. I was an adjutant in an infantry battalion. Before that, I was a student naval aviator, but I never got my wings, so technically, I’m not even a pilot. How do I translate S1? I knew I didn’t want to be a middleman juror or a paper pusher. I didn’t want to be a legal officer. I didn’t want to be a security officer. Those were the things that technically I was as the S1.

I’m in the fashion industry now. So, how do you transition from an S1 billet to going into the fashion industry?

Well, you realize that what you did in the military does not define what you are going to have to do when you leave. You can reinvent yourself and in a very short amount of time, really go down whatever path you want. Very few people get the opportunity that we get to have such a different set of career. Maybe it’s to our advantage.

They’ve just recently started making it so that some of the military training better transitions over, but for a lot of guys, they’ll find that they’re going to have to get retrained anyway. If you were a corpsman in the Marine Corps, in the Navy, it doesn’t necessarily translate over to the civilian world. You’re going to have to go back and you can’t just become an EMT.

You’ve got to go through all that training again, which also sends the signal, do you really want to be an EMT? Maybe you should go into music. You’ve always wanted to do that. Now, you’ve got a great experience and you can pick it up and start something new.

Tom: Yeah. I would just echo everything you just said. When I got out, I started my own publishing company. I have no background in publishing at all, so I also didn’t have to validate myself to anybody because I wasn’t looking for a job, but I will also say this to anybody who is looking for it. Well, one, you can always just start your own thing and there’s nothing stopping you.

Of course, what we will do here is hopefully prepare you to do that through highspeedlowdrag.org and then our premium membership, highspeedelite.com. That’s one of the things we want to focus on.

Second to that is if you are looking for a job and you want to translate your skill set over to a new career, just remember in the military, you have this unfair advantage in terms of you are a leader just by being in the military. People associate leadership with military. They associate a lot of positive attributes with being in the military. So just because your job was something that doesn’t have a direct translation to the civilian world doesn’t mean you can’t find elements of it that tie directly into what your job will be in the civilian world.

Antonio: Yeah. You weren’t a publisher in the Army, were you?

Tom: No, not even close.

Antonio: Okay. Number nine, let’s talk about taking time off. Whenever I was in the Marine Corps, I remember right before I joined 3rd Battalion 1st Marines out at Camp Pendleton, I took a month of leave. It was over a month. It was like 40 days and I went to Ukraine.

Antonio: Okay. Number nine, let’s talk about taking time off. Whenever I was in the Marine Corps, I remember right before I joined 3rd Battalion 1st Marines out at Camp Pendleton, I took a month of leave. It was over a month. It was like 40 days and I went to Ukraine.

I lived in the former Soviet Union for about 30 days just Couchsurfing before it became popular, and that’s where I met my now wife, just enjoying life, living in a whole another culture. I did this in the middle of winter. Now, I didn’t have any responsibility to the military during that time period. I didn’t shave. I didn’t get haircuts. I was off the clock. I was off duty.

Now, in the civilian world, you may have two weeks of vacation, three weeks of vacation, but if you try to just disappear for three weeks and you don’t check your email, you don’t answer your phone, you could find out — you’d come back and you don’t even have a job even though — wait a minute. Didn’t you just earn that time off?

Tom: Yeah. It’s interesting. Actually, that’s one of the things I do appreciate about the military, is those long periods of leave for a month or two. If you could stockpile enough leave dates, that was the best because you truly are off the grid. But in the civilian world, yeah, you can’t do it. Being self-employed, it may be even worse in some cases than being an employee.

At least for me right now, bootstrapping what I’m doing, I don’t have the luxury of taking a day off. I have to be on point at all times every day and that’s fine. I enjoy what I do. I like it, but just be aware that that may be what’s required of you if you want to go that route of self-employment. If you do get a job, yeah, it’s just exactly what Antonio said.

Antonio: Yeah. It depends on the job. There are hourly jobs that are very similar, but I think a lot of you guys listening, you’re not looking for an hourly job. You’re looking either for something that’s salaried and you’re going to be well taken care of or you’re looking to go down the entrepreneurial path.

To defend the entrepreneurial path, I will say once you get past the point of where your business is not — the true definition of a business, in my opinion, is one that doesn’t depend on you. It actually runs on its own and makes money while you sleep.

I, in many ways, have been setting up my business so it runs without me. I have assistants that actually go through my email and help to really cut that down. Whenever products are bought, I’m not involved in any of that. It actually is an automated process. There are many companies that they actually do respect your time off. However, there are many companies out there that the higher you move up, they’re expecting — they’re paying you $100,000 a year — that you are available on weekends.

You’re almost like doctor-on-call. So just be aware that that does come with — they call them the golden handcuffs. Be aware that those things are out there.

Tom: Yup.

Antonio: All right. We’re going to tie the last two together, healthcare and insurance, because both of these were fully covered while you’re in the military and it was a great thing. If you broke an arm, if you broke a leg, you had great healthcare right there even though a lot of people tear up the VA or they talk about the military medical system as not being that great.

Antonio: All right. We’re going to tie the last two together, healthcare and insurance, because both of these were fully covered while you’re in the military and it was a great thing. If you broke an arm, if you broke a leg, you had great healthcare right there even though a lot of people tear up the VA or they talk about the military medical system as not being that great.

In my experience — and I have a number of friends that were Navy doctors — I always thought it was a great experience. I have yet to have a bad experience with active duty military hospitals. I actually have never used my local VA. I have private insurance and private healthcare right now. John, I believe he was talking about it, and Tom, I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on insurance.

By the way, I do actually have my insurance with Navy Mutual, so life insurance, everything. I find that it’s actually much more affordable than anything in the civilian world. If you’ve got insurance that carries on past your time in the military, make sure you have that all set up before you leave because that can save you quite a bit of money.

Tom: Yes. For those who are transitioning, ask questions. Don’t be scared to ask questions to the transition assistant people and organizations that you go through to find out what you actually get when you go because it’s really confusing. I just went through it a year ago literally for the Army. It’s really hard to get just the straight answers of what do I actually get.

When I dug down into it, at least at the time — it may have changed already — I was able to get six months follow-up of healthcare under the VA, then I’d have to transition. Well, maybe even healthcare. Actually, I take that back. I think it was insurance that I was still available for.

Now, a year later, I don’t think I’m good for either of them anymore and I actually have to now look into getting both civilian healthcare and insurance, so I’m awful to ask because I haven’t done it yet, but I will be doing it soon. I’ll keep people posted on the process.

Antonio: Well, I’m sure this is something we can devote an entire section to. We’re never going to be able to keep up with all the changes that go on with the VA. What I would do is I would recommend that if you’re getting out, look at, “Do I have any percentage disability?”

I am technically a 40% disabled Vet. I don’t look it, but I actually had a head injury when I was in the Marine Corps and I had to have my sinuses rebuilt. Because it’s a head injury and all this stuff, I am classified as a 40% disabled Vet, so I got access to a lot of the VA and insurance and things like that. I believe John is a 10%. I don’t know if he’s a 10% or a 0%.

Tom: I think he said 10%.

Antonio: He said 10%?

Tom: Yes.

Antonio: I know that that 0% as well makes a difference. Even though that 0% sounds like nothing, you actually are a bit. So as you’re leaving, make sure that — I thought they were doing a better job with this because it goes from service to service, but I remember when I was leaving, they were doing a pretty good job of trying to make sure people have the right percentage.

Tom: Yeah. Well, I just went through it and I can say in my instance, I thought they did a good job in terms of saying, “Make sure you just say everything that ever happened to you in your military career,” which I did. I just listed everything, which is not too much, maybe like a broken bone and stuff that like or a concussion or whatever, some random stuff like that, but I put it all down.

What’s interesting is even if you got 0%, the cool part about that is you’ll be covered for life if that problem ever turns into something worse. Obviously, I haven’t had to go through that experience of saying, “I broke my foot in the Army and now it’s a problem 20 years later.” I’ve never had to do that, of course, but technically speaking, I should be able to. It should be 100% taken care of.

So for those who are still transitioning, definitely get checked out and make sure you just list everything.

Antonio: There are a lot of areas — again, we could go into this and we’ll probably have entire sections, but you’re always thinking long term and where things are headed.

So we talked about the 11 things that Vets find confusing. If I were to go up to the very top, we first talked about people say one thing and do another. We then talked about narcissism. Then we talked about the importance of physical goods and image, layoffs and being fired. Number five, you’ve got to negotiate your salary. Number six, translating your stories and experiences; seven, business language; eight, how to find a new career path; nine, taking time off; and then ten and eleven, healthcare and insurance.

All right, Tom, anything to add?

Tom: No, it’s good stuff. Actually, for those who are listening, if you found this stuff fascinating, reach out to us maybe and let us know which ones you’d like to hear more about because some of these piqued my interest personally and I’d love to dive into more depth, and we would be happy to create special shows on specific topics. Would you agree, Antonio?

Antonio: Yeah. This is fun. I love going back and talking about it. You can find the detailed articles over at highspeedlowdrag.org. What’s going to be interesting about these podcasts is we’ll be able to go into a little bit of the stories behind it. You get to learn a little bit about our experiences with these because we’re creating this content and we’re printing it based off of your feedback and our experience.

I’d like to be able to share some of the stories with you, why this is something, because we’ve walked this path already and we want to make sure you guys have the tools and that you’re armed so that you can get out there and make a smart decision post-military.

Tom: Absolutely. For those who are listening, check out highspeedlowdrag.org/podcast for the show notes and to check out what else we have to offer when it comes to these podcasts. Also, if you get the chance, rate us on iTunes. We’d love to hear what you think of this podcast.

Antonio: Yeah. We really appreciate it, guys. We’ll see you on the next one.

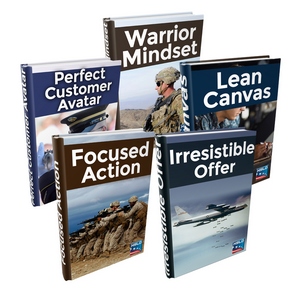

Veterans, your education doesn’t stop here. Go to highspeedelite.com to join the exclusive Veterans Mastermind that will give you the unfair advantage to succeed in both business and life. We have dozens of training courses, HD videos, a private Facebook group, and the chance to interact daily with John and other successful veteran entrepreneurs every month on live hangouts and webinars.

High Speed Elite is more than a mastermind. It’s your ticket to the land of success.

Are you prepared to ignite? Go to highspeedelite.com today to find out more.